Beyond The Continuum

Curated by SAMIA ASHRAF

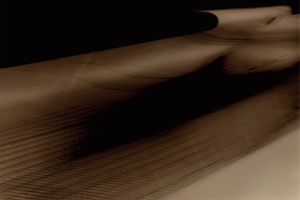

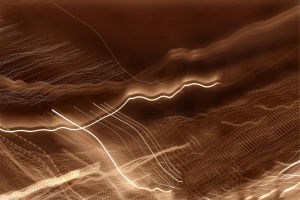

Suspended in time is a single sweeping curve of a musical note, its amber form occupying the composition. An iridescent futuristic plane of cascading hues and bronze, copper and golden traces are silhouetted by movement – through which the translucent layers build gradations of abstraction to suggest a presence of being, a life force continually assembling and disassembling.

An arresting photographic installation, ‘Beyond The Continuum’ comprises 13 pieces, each measuring 63cm x 95cm, by the British artist James Dean Diamond. For this exposition, he transports us to a kaleidoscopic universe of light configurations, where the enfolding works consider time theories, and photons render the metropolis into a dynamic system. Making sense of the world through the interchange of scientific inquiry and science-fiction literature, and in keeping with HG Wells’s novels, Diamond’s Edwardian time traveller’s adventure is an enchanted vehicle to other dimensions.

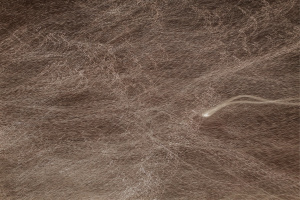

As our protagonist passes through time, we move across a phosphorescent landscape. With partial views of spaces and environments, impressions of the city shift, centuries appear and disappear, while civilisations vaporise. Leaping in scale from micro to macro, one slips into another interval or zone. Disruptive perspectives induce a sense of dislocation as the camera rapidly pans and locks into position.

Approaching his work as reportage, Diamond begins with the real, shooting the streets of London, Brighton and Copenhagen in perennial motion. His vocabulary resides within the urban sublime, expanding further into a significant language. Using the sequence as narrative, this unpeopled vision captures layers of time, evoking the shimmering sand dunes of Arabia, vanishing mirages, optical illusions, and contours resembling buried cities – in a particular piece, a pharaoh’s chariot appears to charge at great speed, which points to the project’s spiritual interest. These lyrical elements of luminous energy effuse with memory, illustrating a Futurist concern for dynamism.

Diamond's investigation corresponds with the contemporary artist Richard Wright, who ‘relates to the architecture of a space mainly through light. I want the work to disperse into the light that shifts and absorbs it. I’m interested in how the material holds light, how this is captured, released or lost.’1 This idea of perception was presented by the early theoretical physicist Ibn al-Haytham (born c965 in Basra), whose insight into the principles of astronomy and mathematics led him to be ‘the first to explain that vision occurs when light bounces on an object and then is directed to one's eyes'.2

The installation also references the Hungarian photographer László Moholy-Nagy’s ‘photograms’ – processed when household objects were placed on to photographic paper and exposed to light sources. Acting as diagrammatic record of this motion, the tonal variation synthesises spatial relationships to produce arrangements belonging to another cosmic sphere. Diamond researches the potential mark-making capabilities of light rays through the lens, directing the attention to the transmission of a polyvalent virtual image to sit beneath the surface of the paper. As time accelerates, the incandescent tectonic folds overlap into a floating orchestration.

Albert Einstein, in his Theory of Relativity (1915) found that space (in its three dimensions of height, width and breadth) and time are interwoven to make the fabric of the universe into a single continuum, space-time. Gravity is a key component in the space-time map, altering the passage of time – moreover, the varying field strength causes time dilation, an actual difference of elapsed time occurring between two points. For example, during the 1930s the clock at the top of the Empire State Building ran faster than its ground-floor counterpart. Presently, satellite atomic chronometers require an annual adjustment of a minus of one second, which further demonstrates time is not a constant. A field teeming with eternal thought has TS Eliot’s profound work ‘Burnt Norton’ (the first poem of the ‘Four Quartets’) infer that time is ‘fundamental to our psyche, indeed our very sense of existence’3, yet perhaps it alludes us.

A philosophy of space and time is also embedded in various indigenous cultures. The Incas’ ‘elastic sense of time’4 proposes that at any given moment one consciousness concurrently holds the past, present and future5. These three strands ‘create simultaneous realities … as though you perceive several realities collectively at once’.6 Central to Aboriginal mythology is ‘Dreamtime’, a multilayered concept which underscores reality. Signifying the foundation of knowledge, pertaining to creation, law and ethics, this is a period in which ancestral figures of supernatural capabilities inhabited the land, as well as a representation of a past, present and future continuum. We may consider our lives to be in a perpetual state of time travel, whether it’s thinking about the/a past, cognisant of the/a present or projecting into the/a future.

A practice defined by a vivid imagination, Diamond’s ongoing preoccupation is to give visual expression to the flux of energy. Envisioning a condition of fluidity, the intricate lines of rhythmic harmony coalesce to illuminate an expanse beyond astrophysics.

1 ‘Domus’ magazine, ‘In conversation with Richard Wright’, October 2015

2 Peter Adamson, ‘Philosophy in the Islamic World: A History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps', 7 July 2016, Oxford University Press, p77

3 Tatsuo Miyajima, ‘Big Time’, Hayward Gallery, London, 1997, p13

4 John Akomfrah, ‘The Airport 2016’, press release, Lisson Gallery, London, January 2016

5 BBC Horizon, Brian Cox, ‘Do You Know What Time It Is?’, Episode 4, 2008/2009

6 Jenny Saville discusses her new body of work, ‘Oxyrhynchus’, Gagosian, September/October 2014, p20

The following works are ‘Untitled’ from the series ‘Beyond The Continuum’ | Dimension: 63cm x 95cm | Medium: C -TYPE | Edition: Eight per piece | 2011